You have completed the first draft of your story. If you’re working toward publication, you probably know this was just step 1. (My post on From Draft to Done can help you understand the process.)

Today’s topic comes to you courtesy of writer-me, who finished the first draft of her novel last week during writing sprints. ~ LZ

Whether you have written a short story, novella, or novel, the purpose of putting the first draft down is telling yourseif the story. Every idea you have may be wonderful, but it’s trying to put these images, emotions, and sensations appearing in your head into words so that someone else can experience this story for themselves where the struggle can lead to something less than wonderful.

Here are 5 tasks you can do to improve the fractured writing to a put-together puzzle with the seams less visible and the story more gripping.

1. Objective distance

Seriously, the most important aspect of self-editing is to get some distance from this being your writing. You need to look objectively at the different elements instead of feeling/thinking “this is my baby, it’s perfect–look at this beautiful moment!” If the moment is more like an off-road that makes readers forget where they were going in the story in the first place, then you need to be willing to do some road construction to fix it. And that might mean cutting off that sidetrip.

I recommend a week for every 10,000 words you wrote. If you can’t do that, for whatever reason, at least give yourself a couple weeks by distracting your brain with reading or writing something entirely different. Editing takes an entirely different method of thinking, so it’s not great to just slip from editing to writing, or writing to editing willy-nilly.

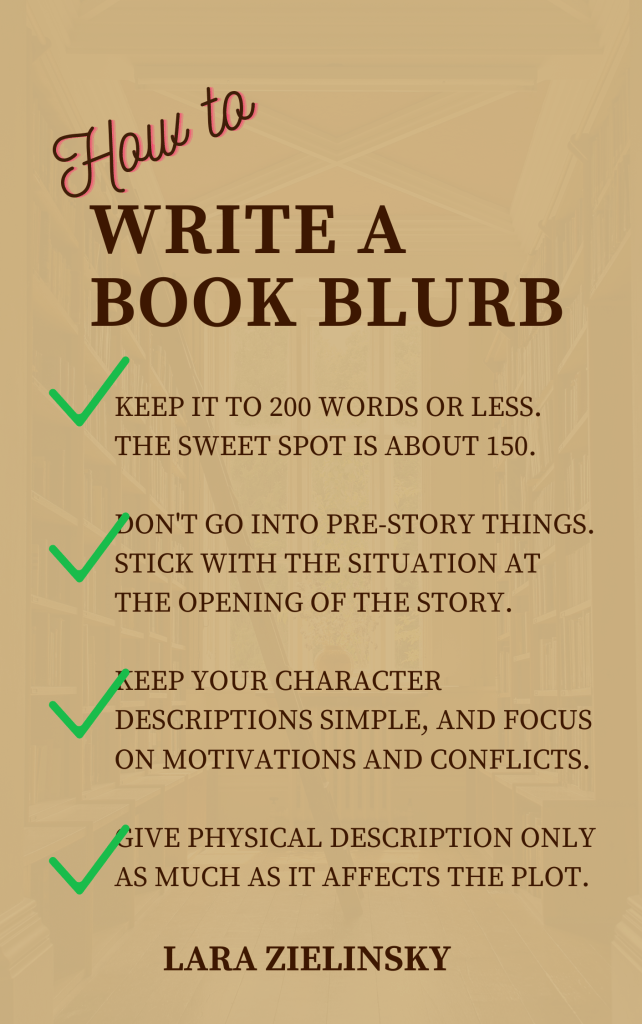

2. Synopsis, then blurb

synopsis

A synopsis is 3-5 pages explaining the story events, the conflicts, and the emotional run line, from beginning, through the middle, all the way to the end. You want to write the synopsis BEFORE you reread.

Read that again. Write the synopsis WITHOUT rereading your story. The distance you gained by following task 1, will mean you will only recall the moments that impacted progress dramatically. It’s going to help you see each scene separately from the whole, and develop a form of checklist for locating those scenes not moving the story forward and thus can be deleted or may need heavy revision–like a character’s scene goal–to remain. Some information may need to be folded into other scenes, but the whole scene itself obviously isn’t powerfully moving the story forward because you, who even wrote it, couldn’t recall that it’s there.

The summary also is useful for more than just editing — if you’re planning to traditionally submit, you will have it for your query package.

blurb

Writing the blurb yourself is also an exercise in figuring out the important details about the characters’ backstory, goals, and motivations, gaining something of a reference sheet, so you can be sure these things are on the page. Especially if you were a pantser for the first draft, you need something that sheds light on what is consistent about the characters, and what might need to be made consistent. This includes the proper spelling of all variations of their name (first, last, nicknames, and even who calls them which), physical details, too, and background, family history, attitudes toward various things. Let’s take a simple example:

Did you write the MC as having a sibling in the first chapter, only for the sibling to disappear in the family gathering in chapter 22? Fixing that, is of course, going to take either, they have no sibling (remove the references in chapter 1) or the sibling isn’t present for X reason that you will have to state in chapter 22.

The blurb is also useful to have. You’ll have your short form pitch for a publisher or agent, or this will form the basis of marketing material when you publish independently.

Copy editors make these same notes, often compiling them in a style guide when they edit your work. If you have these notes, you can provide them to the copy editor for consistency.

3. Make notes on the first read-through

Going slowly, scene by scene, read through your draft and take notes about what each scene is doing. Consider these issues as you look at each scene in isolation. Try to only do one, maybe two scenes in a sitting.

- a) Is this scene/event mentioned in your summary? If not, could it be summarized in a single sentence/paragraph as something that happened “previously” or even removed entirely? If the details of the scene are meant to impact the character, then it probably will need to stay, but you might also consider whether the scene is showing that impact. Is the character’s interiority showing their increasing discomfort, anxiety, feelings of disruption to the status quo?

- b) Is this scene establishing, developing, or hampering the character’s goal? It’s very important that simple sequences of events that are not interrupted, don’t change the character’s feelings or attitudes, or would be common for anyone in that situation are summarized, so that the reader gets the spotlight quickly focused on the moments that matter. You don’t need to show them getting in their car, starting the engine, and driving across town to the spot for the dinner date, if nothing interrupts these things. What IS important is how they are processing things in the context of the coming activity. Here’s an example using a dinner date: “Driving across town for his date, he anxiously fretted at every red light. He didn’t want to be a person she perceived as late to things.”

- c) Is this scene happening in a clear setting/space? Are the characters–meaningfully, remember point b above–interacting with the setting: picking up things, walking around, looking around? If they aren’t supposed to notice their setting because they are focused on what they’re doing with another character, is the POV interiority (thoughts and feelings) showing this fixation/focus?

- d) Is all the detail consistent with the character’s physicality and physical abilities? Did the gunshot victim just get up and walk around like nothing happened or sit up in the hospital bed and hug someone? If there is chronic illness or disability, is the character’s behavior consistent with someone in this situation — if you don’t know, get a sensitivity reader for the scene(s).

- e) Is the depiction accurate for the communities in which the character moves or identifies? Is their word choice on point? Is their interiority individualized, or could it be perceived as stereotypes? If you don’t know, get a sensitivity reader!

4. Make changes to interconnected scenes first

Now that you have a list of notes of changes that probably need to be made, you should group them and sort them into a priority order. Note, scenes that may need to go, should be done LAST. What you choose to do first, depends on how you presented scenes: single POV, multiple POVs.

For dual or multiple POV stories, where there’s scenes from different character’s POV, back and forth, pick one POV to examine first. Then do the other. However, for single POV stories, go through groups of scenes that take place in the same physical locations or are furthering the same subplot.

Skipping back and forth between scenes in different character POVs runs the risk of making your characters all act and sound the same.

Final thoughts

Note, I suggest no word-level edits here, except for the lingo comment in 3e. This self-editing advice is entirely developmental/structural. Between you and your beta readers and sensitivity readers, you are checking that what you’ve written is telling a cohesive, developing story with characters that are engaging and consistent in their details, movement, goals, and speech.

Getting sensitivity readers is best done at this early stage in the story correction for the simple reason that if a whole scene needs to be rewritten or even deleted, you don’t want to already have paid someone to correct grammar and punctuation.

~ Lara

Discover more from LZ Edits | Editing Services

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.