A story is considered complete if it contains complex vivid characters with goals moving in a setting described through all or at least many different types of sensory details, and the plot logically follows from an inciting incident, through several logical complications, reaching a climax, and settles many reader questions by the time the concluding pages are reached.

But what elevates one story from “complete” to “compelling” is pacing and tone. The pacing and tone should fit the story, seamlessly blending all the elements into a tapestry that gives readers emotional connection to the characters and their travails.

This is part 1 of 2 posts discussing these crucial elements of story building. Go here for a deep dive into tone.

What is pacing?

Pacing is the rhythm of how a story’s events unfold, when new details, new wrinkles, or character triumphs and setbacks are introduced. Pacing is not about word count, or this chapter or that chapter is “too early” or “too late” to introduce or resolve some point of conflict. Pacing is about the length of story time that carries the character forward, the time it takes building anticipation, create anxiety, or how long between a foreshadowing and its payoff.

In contrast, story time is measured not in chapters or scenes, but in the days, weeks, and months the character is moving through. Every time you write “a week later,” you are saying that nothing compelling happened for a week. If a character is still angry, anxious, upset, that could be jarring – unless the story details why they continue to feel these emotions so long after the event(s) that caused them.

Too fast

If you have ever wondered “how could he possibly be thinking she’s the love of his life if they’ve only met a couple times”, then the story’s pacing is off. Nothing on the page convinced you of why this person would believe that. The writer “hopped over” the details.

This applies to all characters, even those who are stalkers, obsessives, and even shifter “fated mates.” You have to explain by dropping properly paced details that support the “instant” conclusion. If a character is physically attracted to someone, take the time to note the specifics of that attraction. In a romance, emotional connection is built through experience, and so, too, that requires the specifics of attraction. They play brain games and he appreciates the way she thinks. He tries a pick up line, and she scoffs at him. But she didn’t shoot him down; so he tries again, with something more genuine this time. That’s properly pacing the build of attraction.

Too slow

There is the cat-n-mouse that takes up most of the story space, or the slow burn romance, and then there’s just ridiculous dragging. If you are repeating the same details, lessons, or consequences over and over again, that’s a sign your plot is moving too slow. Yes, characters can be slow on the uptake (figuring out that someone’s into them) but make the situations — and actions that signal attraction — slightly different each time. Your character should experience enough dots to connect things. But you shouldn’t frustrate your readers.

Just right

How many times have you watched a movie introduce one lead, and then another, and said to yourself “oh those are the two leads, of course, they’re going to get together.” But as the story progresses, you begin to worry. The “getting together” part seems fraught with problems, setbacks, and maybe there’s even a refusal of one character to be involved, or in the same room, with the other at all? That shows the story is properly paced.

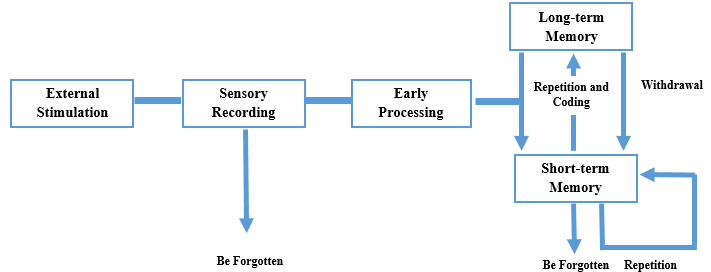

This diagram points out that something happens externally. The character then processes it through their senses. The character makes some early conclusions, which may be premature, or even wrong. Then the character commits their learning to long-term memory or uses what they learn in the short-term.

Why do you describe the chasm’s vast expanse and its dizzying thousand-foot drop before you describe the rickety bridge that could allow the character to cross? Because you have to introduce the problem and the stakes to up the ante. Only after that can you introduce a possible solution. That is how pacing works.

And so you don’t get overwhelm, ponder that for a while. I’ll discuss tone next.

~ Lara

Discover more from LZ Edits | Editing Services

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.